What's going on with Fermi's paradox?

How this physicist's harmless question opened the gates for an existential crisis of cosmic proportions

I've done a lot of talking about Enrico Fermi's worry-machine without talking about what it is and why it matters.

This post is a quick run-down of the major issues with Fermi's Paradox.

Highly opinionated, naturally.

Fermi's paradox began, according to legend, with an off-handed question from physicist Enrico Fermi during a lunch-time chat about aliens and UFOs:

"Where is everybody?"

The reasoning being, if aliens are out there and space travel is physically and economically feasible, then why aren't they here?

It seems like a harmless question, doesn't it?

Yet it's kept people lying awake at night...

Staring up at the sky with awe and horror...

Writing novels about aliens smashing up Earth because of game-theory calculations...

And it might be one of the most pressing problems of our age.

Fermi's paradox isn't just a puzzle about aliens.

It touches on our deepest beliefs about the nature of life, mind, and human existence.

There's a lot of stuff packed into that innocent little question.

My starting point is a wonderful book by Milan Cirkovic, called The Great Silence.

Cirkovic nerds out on Fermi's paradox like none other.

Cons: It's meant for an academic audience. It's readable academese, but academese it is.

Per RP editorial policy, what follows here is plain language.

What's Fermi's paradox really asking about?

Popular portrayals notwithstanding, Fermi's paradox isn't asking why there aren't aliens zipping by in flying saucers.

The actual thought-experiment behind Fermi’s paradox goes much deeper than that.

When put as the question, “why haven’t they visited us?”, the whole idea sounds like the stuff of kooky conspiracy theories.

You're just begging for answers like “well how do you know they haven’t?” or the opposite, when the skeptics explain all the reasons why we we shouldn’t expect there to be aliens zipping around in flying saucers.

I never gave this problem too much thought until I found Cirkovic’s book a few years back.

The real shiv of Fermi’s paradox isn’t why we don’t have alien visitors hovering in saucers over the world’s major cities.

No, the problem has deeper roots in the observations of astronomy — especially the findings over the last 30 years about the frequency of planets around stars — and a handful of reasonable assumptions about how intelligent beings might act.

The strongest form of Fermi’s paradox isn’t the “why aren’t they here?” question.

The problem isn’t even that there are no civilizations that have interstellar travel.

No. It’s about...

What we should be able to detect from other technological civilizations

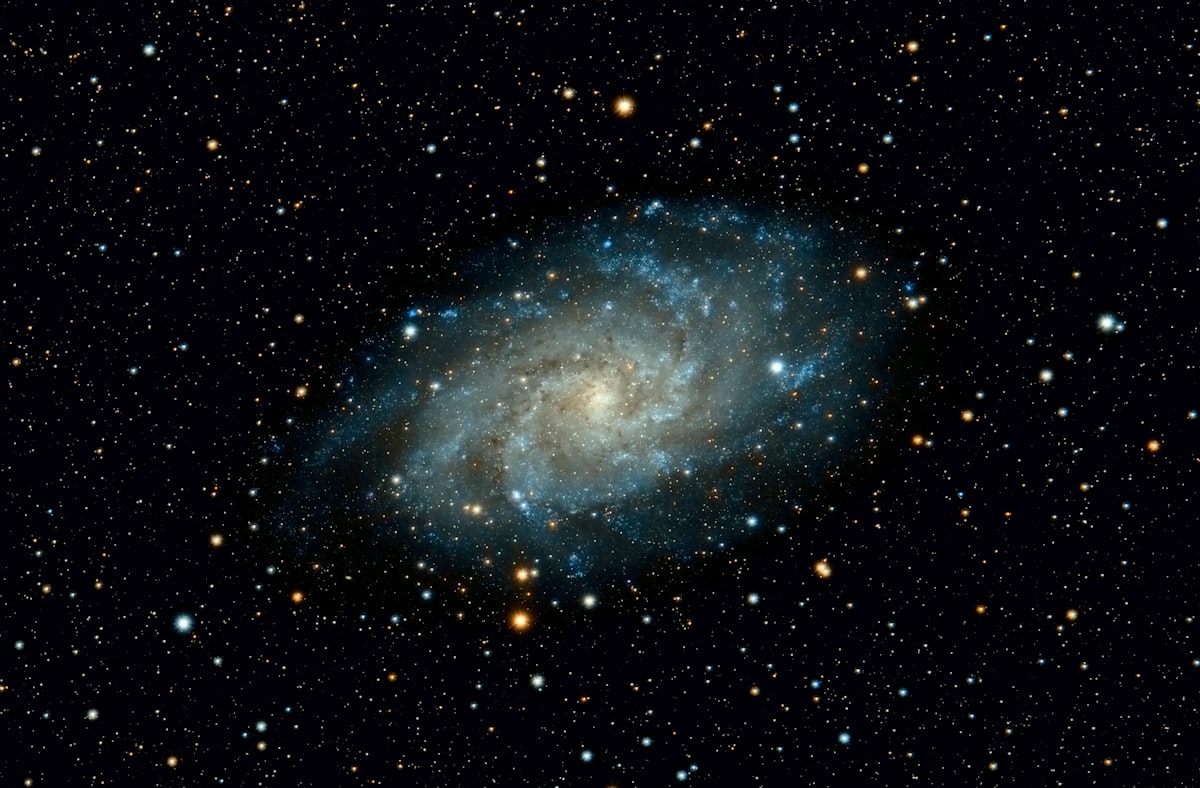

When we look out at the night sky, tens of billions of light years…

…there’s nothing.

Not a signal. Not a sign of propulsion. No antimatter farms. No transmissions. No self-replicating probes. Nothing.

You might think, so what? It’s expecting a lot to see signs of a high-tech civilization.

That’s a fair response. They might not use radio, they might not be sending out signals, they might be using tech that's not easily detectable, they may not be doing cosmic mega-engineering, maybe they discovered new physics that we don't understand... and on and on.

But that doesn’t work.

Why? Because of a principle called non-exclusivity.

Non-exclusivity was introduced and discussed in some detail by Brin in his seminal 1983 review article. According to this construal, it is simply a principle of causal parsimony applied to the set of hypotheses for resolving Fermi’s paradox: we should prefer those hypotheses which involve a smaller number of local causes.

What this means is that, while we could expect the random course of events to take out any particular civilization, we wouldn’t expect it to take them ALL out.

For a concrete example, take the Cold War. Nuclear damnation was a serious option in the cards for awhile there. Had history gone just a little different, we’d be toast as a species.

But ALL of them? Everywhere in the whole universe? That defies belief… somebody, somewhere, would have made it through or around that storm, if only by chance of the odds.

So why don’t we see any signs of this?

That’s Fermi’s paradox in its strongest form.

What's the paradox here?

When we talk about paradoxes, the common examples come from logic or math or Back to the Future.

Consider the Liar's Paradox:

This sentence is false.

If you take that sentence at its word and assume it's making a true statement, then it's false. The truth undermines itself by asserting its own falsehood.

That's troubling.

Fermi's Paradox isn't this kind of self-referential glitch.

So how did it get that name?

Let's rewind and talk about the astronomical science that led to this point.

Based on work by Charles Lineweaver, the current best guess is that Earth-like planets could have begun forming as long as 9 billion years ago.

The median age of such planets is around 6.4 x 10^9 years.

That's a good deal older than our own solar system, with our own sun clocking in at 4.5 x 10^9 years.

That’s a BIG gap.

Almost 2 billion years between the median age of planets in the galaxy and the age of our solar system

Let’s be clear about how big this is. That’s a number that concerns stars and geological eras on Earth.

With all those planets, we should expect there to be civilizations, possibly lots of them, unless for some reason life is incredibly rare. But we have no compelling reasons to think that it is. Quite the opposite, there's lots of evidence suggesting that life is common.

Then there's the time. These civilizations have had so much time to do things we can barely dream of.

Here's the next step.

Astronomy, like all natural sciences, depends on a system of background assumptions which aren't discovered by science.

These are the methodological rules that allow scientists to do good science.

Rules like the Copernican principle, which says that Earth, and human beings, are more or less typical, unexceptional, not-special occupants of the universe.

Nobody discovered the Copernican principle. It's not a fact of a scientific theory. Copernicus himself didn't "discover" this idea. He put out there as a postulate that helped explain some strange features of planetary motion that the existing Ptolemaic cosmology didn't have much luck with.

The Copernican principle is a philosophical assumption that allows science to create theories with more explanatory power.

So, if we accept the Copernican principle, we’d expect that life is not unusual...

That the average age of civilizations to be much older than ours…

And on a vast time-scale, significant against the age of our sun.

That’s the paradox.

All the facts we know, combined with our most reasonable assumptions, tell us that we should expect signs of these older civilizations…

And there’s nothing.

They’re all dead? They don’t last that long?

Okay. But you mean not one of them sent out self-replicating devices? Not one of them sent out a signal that we’d detect? Not one of them decided to rig up Christmas lights around the core of their galaxy?

That defies belief.

That should terrify you.

The Great Silence implies one of two uncomfortable thoughts

The first option is that something is badly wrong with our empirical studies of the universe. This seems unlikely. What with all our new-fangled telescopes, astronomy's gone a long way in the past couple of decades.

If we were badly wrong about the hard empirical data, the mistake probably isn't in the observations alone. It would have to be deeper down, either in certain basic theories, or some of the other assumptions we made to get that data...

Which leads to the second option: that one or more of the working methodological assumptions is wrong.

Copernicanism, for example, suggests that we’re more or less typical of events in the universe. If it turns out that, for whatever reason, the existence of homo sapiens is a wildly improbable occurence, then we might not reasonably expect to find anybody else out there.

You can use your own imagination for what it would mean if we have to throw that out.

And that's not all.

A skeptic could have a hard look at how we frame the Copernican principle.

By assuming that we, and our position in the universe, are not unusual or atypical or any kind of outlier...

Modern-day Copernicans might be -- ironically -- anthropomorphizing their results

Copernicanism aims to be the ultimate non-anthropormorphic principle. By holding that we humans have no special perspective, we can get at objective truths without our subjective biases.

That works for simple stuff like figuring out planetary movements or how atoms work.

But with a quick flip of this idea in your mind you can see it from a different angle:

By assuming we are typical and ordinary "from the perspective of the universe", we can easily conclude that much of the universe works according to the way we see it.

Rejecting anthropocentrism makes it easy to assume that our point of view is universal.

If that's true, we could be wildly mistaken about the kind and variety of life out there... how intelligence works... and so much more.

Now isn't that wild?

A very Lovecraftian take on our cosmic predicament.

The Intelligent Design people will have a field day. The fertile imaginations of the pulp writers of weird fiction won't seem so silly.

Whatever's going on with Fermi's paradox, it's weird and the consequences are likely to be existentially unsatisfying.

This isn't just about aliens and UFOs. The answers to this problem touch on our deepest ideals and understanding of life and mind.

Should the resolution to Fermi's paradox turn out to be “we all die alone in the mud”, bleakness aside, that tells us a lot about the prospects of intelligent species.

Either way you shake it, Fermi’s paradox is a pretty big deal for the fate of life and mind.

If you write SFF that touches on any of these matters, you'll want to keep this in your mind.

Fermi's paradox shows us that something is deeply wrong with our understanding of the cosmos and intelligent minds

By the way – If you liked this article, you'll get to read all the member-only posts if you join us.

Want to leave a comment? You'll need to join us on the inside with a bonus perk for members.

You get to be a part of the private rogue planet community. Leave your thoughts and hang out with other SFF Heretics on the inside, away from the screaming mess of Twitter and the privacy-thieving jumble of Facebook.

There's no charge (yet) to become a member, so click here and join now.