The missing human element in galactic settlement scenarios

Solving the problem of space travel isn't about getting the right rockets.

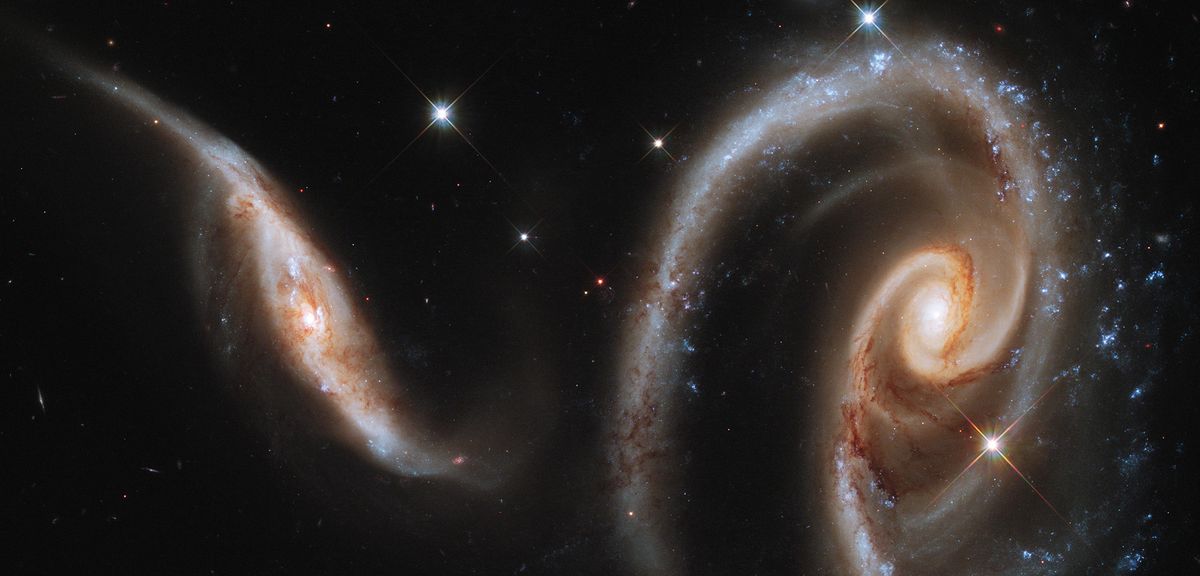

One of the more frustrating things about writing space opera is the awe-inducing size of the frontier.

Humans don't have any easy frame of reference for this. With perceptual abilities evolved to cope with a handful of environmental constraints found within a kilometer of the Earth's surface, the homo sapiens nervous system doesn't do well with astronomical numbers.

Which makes for easy analogies with other modes of travel. Sailing ships and airplanes give us most of our metaphors for space travel, even though the mechanics of rocketry have been well-studied for close to 100 years.

But there's the trouble. Any trip into space, barring some miraculous revolutions in our best understanding of physics, is going to suffer from the many maladies of a Newtonian and Einsteinian universe. (Which is before we even consider the options for finding livable worlds around other suns.)

All of which make the colonization trope unlikely. There's a romantic appeal to the rough-edged pioneer striking out into the unknown, bringing civilization to the wilds, which is why it's persisted as a theme.

This situation is also why space opera today almost has to adopt an alternative universe or alt-history conceit if it's going to go anywhere. I don't mind playing in Rice's Venus, myself, but even I can't delude myself into treating those stories as a plausibly scientific or realistic scenario in the way a reader could have in the 1930s.

The realities of mounting a serious colonization project make this unlikely. Still, there's always hope – and we can always dream.

A post over at Centauri Dreams looks at some of the mechanics of galactic settlement using some conservative numbers:

Ships are launched no more frequently (from both the home system and all settlements) than every 0.1 Myr — every 100,000 years;

Technology persists in a given settlement for 100 million years before dying out;

Ship range is roughly 3 parsecs, on the order of 10 light years.

Ship speeds are on the order of 10 kilometers per second; in other words, Voyager-class speeds. “We have chosen,” the authors say, “ship parameters at the very conservative end of the range that allows for a transition to Type iii.”

The article links to a pretty video showing the projected spread of civilization from these starting values.

I don't quibble over the math, which is not my area of interest.

But I do wonder about the "X-factor" always missing from these assumptions.

It's well and good to talk about what "we" can do. "We" can travel the stars, colonize the galaxy, create a utopia on Earth, end poverty and hunger and...

The trouble with the grand "we" was captured so well in the immortal line attributed to the Lone Ranger's sidekick Tonto:

What do you mean "we", kemo sabe?

Launching a colony ship once every 100,000 years may sound trivial to a space-going civilization – until you give a moment's thought to what your great great great (etc.) grandparents were doing 100,000 years ago.

To imagine a society even surviving for that long is already a feat of the imagination.

To imagine that society remaining organized around an intention to expand across the galaxy over multi-million year time scales?

Who is the "we" that's going to keep all this together?

The mechanics of space travel seem like a much easier problem to solve than the quirks of human psychology.

Which brings up a whole host of story questions about the future condition of homo sapiens, doesn't it?

PS – If you enjoy these posts, why not subscribe? That way you can receive them directly in your inbox... and you'll get the members-only posts.

There's no charge (yet) to subscribe as a free member, so click here and join now.